Facts about Alfalfa

First, as a member of the legume family, alfalfa has a mutualistic relationship with nitrogen-fixing bacteria, allowing it to convert atmospheric nitrogen into a usable form.

Alfalfa can be sown in spring or fall, and does best on well-drained soils with a neutral pH of 6.8–7.5.

Most of the improvements in alfalfa over the last decades have been in disease resistance, improved ability to overwinter in cold climates, and multileaf traits.

After the alfalfa has dried, a tractor pulling a baler collects the hay into bales.

Alfalfa pollination is somewhat problematic because the keel of the flower trips to help pollen transfer to the foraging bee, striking them in the head.

The leading alfalfa growing states (within the United_States) are California, South Dakota, and Wisconsin.

Alfalfa is considered an "insectary" due to the large number of insects which are found there.

Disease resistance is important because it improves the usefulness of alfalfa on poorly drained soils, and during wet years.

Alfalfa has been spread by people throughout the world, ensuring its survival as a species, and bees even have been imported to alfalfa fields for pollination purposes.

The bees receive a food source from the flowers of the alfalfa, while the pollination allows the cross-fertilization necessary for reproduction of the plants.

Alfalfa is also susceptible to root rots including phytophora, rhizoctonia, and Texas Root Rot.

Dehydrated alfalfa leaf is commercially available as a dietary supplement in several forms, such as tablets, powders and tea.

Alfalfa is widely cultivated for hay and pasture for livestock, but also is used as source of food for people and as a medicinal herb (Longe 2005).

Nesting is in individual tunnels in wooden or plastic material, supplied by the alfalfa seed growers (Milius 2007).

When used as feed for dairy cattle, alfalfa is often made into haylage by a process known as ensiling.

The legumes are traditionally classified into three subfamilies (in some taxonomies these are raised to the rank of family in the order Fabales), of which alfalfa belongs to the subfamily Faboideae or Papilionoideae.

In areas where drying down of the alfalfa is problematic and slow, a machine know as mower-conditioner is used to cut the hay.

Second, alfalfa has a mutually beneficial symbiotic relationship with bees.

Some pests such as Alfalfa weevil, aphids, and the potato leafhopper can reduce alfalfa yields dramatically, particularly with the second cutting when weather is warmest.

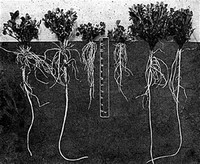

Alfalfa has a very long, deep (two to five meters) root system (Longe 2005); the long taproot may even reach 15 meters deep.

Today the alfalfa leafcutter bee is increasingly used to circumvent this problem.

Alfalfa is an excellent source of vitamins A, D, E, and K, and is high in protein, and also contains trace amounts of such minerals as calcium, magnesium, iron, phosphorous, and potassium (Longe 2005).

When grown on soils where it is well-adapted, alfalfa is the highest yielding forage plant.

Modern alfalfa varieties have probably a wider range of insect, disease, and nematode resistance than many other agricultural species.

Alfalfa lives from three to twelve years, depending on variety and climate.

Most alfalfa cultivars contain genetic material from Sickle Medick (M. falcata), a wild variety of alfalfa that naturally hybridizes with M. sativa to produce Sand Lucerne (M. sativa ssp.

Alfalfa is native to Iran, where it was probably domesticated during the Bronze Age to feed horses being brought from Central Asia.

Alfalfa seed production requires pollinators to be present in the fields when in bloom.

Alfalfa sprouts are used as a salad ingredient in the United States, Australia and New Zealand.

Alfalfa is a plant that exhibits autotoxicity, which means that it is difficult for alfalfa seed to grow in existing stands of alfalfa.

A smaller amount of alfalfa seed is pollinated by the alkali bee, mostly in the northwestern United States.

When using farm equipment rather than hand-harvesting, the process begins with a swather, which cuts the alfalfa and arranges it in windrows.

Alfalfa's deep root system and ability to fix nitrogen also makes it valuable as a soil improver or "green manure" (Longe 2005).