Facts about Berkeley

Theologically, one consequence of Berkeley's views is that they require God to be present as an immediate cause of all our experiences.

Far from representing a defense against skepticism, said Hume, Berkeley’s views directly led to it.

Berkeley’s thought is a continuation of Locke’s Empiricism, but Berkeley is much more extreme and, it must be admitted, logically consistent.

On June 11, 1731, "Dean Berkeley baptized three of his negroes, 'Philip, Anthony, and Agnes Berkeley'" (The bills of slave can be found in the British Museum (Ms. 39316); qtd.

Berkeley denies that things can have any existence outside of the perception we have of them.

Berkeley thus challenged the Newtonian concept of matter as an ultimate given, leading to a reduction of reality to what can be physically measured, without asking further questions.

Instead, he strongly opposed it because, unlike Berkeley, he believed in the reality of the material world.

Berkeley’s views need to be understood in the framework of his reaction to the advent of Newtonian physics and their mechanical explanation of the world.

Luce, the most eminent Berkeley scholar of the twentieth century, constantly stressed the continuity of Berkeley's mature philosophy.

Berkeley regarded his criticism of calculus as part of his broader campaign against the religious implications of Newtonian mechanics—as a defense of traditional Christianity against deism, which tends to distance God from worshippers.

On the other hand, Berkeley's thought falls into the category of what could be called divine solipsism: there is nothing much else than God himself in Berkeley's universe.

The philosophy of David Hume concerning causality and objectivity is an elaboration of another aspect of Berkeley's philosophy.

On October 4, 1730, Berkeley purchased "a Negro man named Philip aged Fourteen years or thereabout."

Berkeley’s immaterialism perfectly fit Schopenhauer’s contention that the world is nothing else than our representation on the level of knowledge.

Berkeley’s theory states that one can only directly know sensations and ideas of objects, not abstractions such as "matter."

Berkeley lived at the plantation while he waited for funds for his college to arrive.

A good example of Berkeley's theistic absolutism is his understanding of the notion of cause and effect.

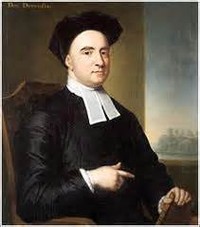

George Berkeley’s name in the history of philosophy is linked to the notion that “to be is to be perceived” (esse est percipi), which summarizes his subjective idealism and immaterialism.

Schopenhauer wrote: "Berkeley was, therefore, the first to treat the subjective starting-point really seriously and to demonstrate irrefutably its absolute necessity.

On the other hand, Berkeley expresses no doubts about the perceiving subject (as Descartes does with his Cogito).

Berkeley's A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge was published three years before the publication of Arthur Collier's Clavis Universalis, which made assertions similar to those of Berkeley.

The fact that the main works were re-issued just a few years before Berkeley's death without major changes also counts against any theory which attributes to him a volte face.

George Berkeley was born near Kilkenny, Ireland, the eldest son of William Berkeley, a cadet of the noble family of Berkeley.

The city of Berkeley, California is named after him, but the pronunciation of its name has evolved to suit American English.

Whereas Berkeley had meant to underline God’s absoluteness, they felt that his views undermined our certainties about reality.

No serious philosopher has ever straightforwardly supported such a position, but Berkeley seems to come dangerously close.

George Berkeley (March 12, 1685 – January 14, 1753), Anglo-Irish philosopher and Bishop of Cloyne, was one of the three great British Empiricists of the eighteenth century (following John Locke and preceding David Hume).

Berkeley is both the epigone of a past age and a still clumsy precursor of the critical method perfected by Kant, an empiricist and a dogmatic idealist.

Berkeley’s contemporaries, including Voltaire and David Hume who sometimes praised his immaterialism, did so for entirely contrary reasons.