Facts about Courage

Courage is also popularly recognized and discussed as an important virtue in various aspects of social life.

A mercenary, for instance, is not courageous because his motive for fighting is not the good of the homeland or the welfare of his fellow countrymen; rather, his motivation is for money.

The soldier who exemplifies courage, then, is not merely willing to risk his life by rushing forward in battle.

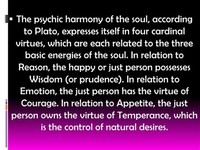

The medieval schoolman took over Aristotle’s depiction of courage and the classical view that it is one of the four “cardinal” virtues (along with wisdom or prudence, temperance, and justice).

Only the soldier willing to sacrifice his life for the noble cause is courageous.

Courage is the virtue, then, which controls the appetites (in an individual) or the greed of the moneymakers (in the city).

Aristotle provides a more detailed account of the virtues and courage in his Nicomachean Ethics.

Whereas the cowardly or rash soldier will react blindly by either fleeing the danger or rushing toward it, the brave person will remain sufficiently composed so as to perform the courageous act.

The virtue of courage, then, is that disposition which allows the soldier to think wisely in the face of danger.

The virtue of the auxiliaries (whose job is to protect the city) is also courage.

Courage, then, is linked to fortitude in being able to hold one’s ground or stand up for one’s convictions regardless of circumstance.

Courage, for example, lies between the vices of cowardliness and rashness.

Existentialists in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries approached courage in relation to man’s attempt to restore his authentic existence.

So although the mercenary may show a certain strength and clear-sightedness in the heat of the battle, his actions are not courageous.