Facts about Tlingit

Like other Northwest Coast peoples, the Tlingit carve totem poles and hold potlatches.

The flesh decays quickly, and in most cases has little spiritual value, but the bones form an essential part of the Tlingit spiritual belief system.

Considering that most of the explorers visited during the busy summer months when Tlingit lived in temporary camps, this impression is unsurprising.

The primary staple of the Tlingit diet, salmon was traditionally caught using a variety of methods.

A saying amongst the Tlingit is that "when the tide goes out the table is set."

The moieties provide the primary dividing line across Tlingit society, but identification is rarely made with the moiety.

Tribe names define regions of dwelling; for example, the Sheet'ka K-waan (Sitka tribe) is the Tlingit community that inhabits Sheet'ka (Sitka).

Food is a central part of Tlingit culture, and the land is an abundant provider.

A more practical explanation follows from the tendency of the Tlingit to harvest and eat in moderation despite the surrounding abundance of foodstuffs.

The most obvious is the division between the light water and the dark forest which surrounds their daily lives in the Tlingit homeland.

The term aan s'aatн is now used to refer to an elected city mayor in Tlingit, although the traditional position was not elected and did not imply some coercive authority over the residents.

On June 19, 1935, an act of Congress was passed to recognize the Tlingit and Haida people as a single federally recognized tribe.

Between 1886-1895, in the face of their shamans' inability to treat Old World diseases including smallpox, most of the Tlingit people converted to Orthodox Christianity.

The Old Man dotes over his grandson, as is the wont of most Tlingit grandparents.

The Tlingit (IPA: /'kl??k?t/, also /-g?t/ or /'tl??k?t/ which is often considered inaccurate) are an Indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest.

The traditional Tlingit house, with its solid redcedar construction and blazing central fireplace, represented an ideal Tlingit conception of warmth, hardness, and dryness.

To this day, Tlingit regalia, language, clan structure, political structure, and ceremonies including beliefs are evident in all interior culture.

The Tlingit kinship system, like most Northwest Coast societies, is based on a matrilineal structure, and describes a family roughly according to Lewis Henry Morgan's Crow system of kinship.

Each house was led by a "chief," in Tlingit hнt s'aatн "house master," an elder male (or less often a female) of high stature within the family.

Tlingit people as a whole participate in the commercial economy of Alaska, and as a consequence live in typically American nuclear family households with private ownership of housing and land.

Tlingit culture, being the fiercest among the coastal nations due to their northernmost occupation, began to dominate the interior culture as they traveled inland to secure trading alliances.

The Tlingit rather quickly appreciated the trading potential for valuable European goods and resources, and exploited this whenever possible in their early contacts.

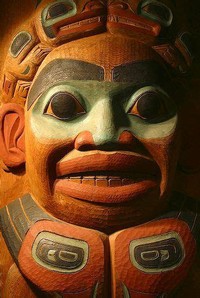

Traditional colors for the decorative art of the Tlingit are generally greens, blues, and reds, which can make their works easily recognizable to the lay person.

The maximum territory historically occupied by the Tlingit extended from the Portland Canal along the present border between Alaska and British Columbia north to the coast just southeast of the Copper River delta.

The Tlingit are famous for their carved totem poles made of cedar trees.

Today, the K'alyaan (Totem) Pole stands guard over the Shis'kн Noow site to honor the Tlingit casualties.

Water serves as a primary means of transportation, and as a source of most Tlingit foods.

Clan sizes vary widely, and some clans are found throughout all the Tlingit lands whereas others are found only in one small cluster of villages.

From this regular travel and trade, a few relatively large populations of Tlingit settled around the Atlin, Teslin, and Tagish lakes, the headwaters of which flow from areas near the headwaters of the Taku River.

Tlingit traders were the "middlemen" bringing Russian goods inland over the Chilkoot Trail to the Yukon, and on into Northern British Columbia.

After the introduction of Christianity, the Tlingit belief system began to erode.

The Tlingit fled north and established a new settlement on the neighboring Chichagof Island.

Heat, dryness, and hardness are all represented as parts of the Tlingit practice of cremation.

The Russian victory was decisive, and resulted in the Tlingit being permanently displaced from their ancestral lands.

Art and spirituality are incorporated in nearly all areas of Tlingit culture, with even everyday objects such as spoons and storage boxes decorated and imbued with spiritual power and historical associations.

Historically, marriages amongst Tlingits and occasionally between Tlingits and other tribes were arranged.

The eight long bones are emphasized because that number has spiritual significance in Tlingit culture.

Another Spanish expedition, led by Alessandro Malaspina, made contact with the Tlingit at Yakutat Bay in 1791.

When a Tlingit references their mind or feelings, he always discusses this in terms of axh toowъ, "my mind."

Game forms a sizable component of the traditional Tlingit diet, and the majority of food that is not derived from the sea.

The people followed them down under the glacier and came into Lingнt Aanн, the rich and bountiful land that became the home of the Tlingit people.

Herring (Clupea pallasii) and hooligan (Thaleichthys pacificus) both provide important foods in the Tlingit diet.

When a respected Tlingit dies the clan of his father is sought out to care for the body and manage the funeral.

The Tlingit clan functions as the main property owner in the culture, thus almost all formal property amongst the Tlingit belongs to clans, not to individuals.

Another series of dichotomies in Tlingit thought are wet versus dry, heat versus cold, and hard versus soft.

All species of salmon are harvested, and the Tlingit language clearly differentiates them.

The Tlingit are a matrilineal society who developed a complex hunter-gatherer culture in the temperate rainforest of the southeast Alaska coast and the Alexander Archipelago.

Herring eggs are also harvested, and are considered a delicacy, sometimes called "Tlingit caviar."

The Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska was established in 1935 to pursue a land suit on behalf of the Tlingit and Haida people.

Soon the Tlingit clan and political structure, as well as customs and beliefs dominated all other interior culture.

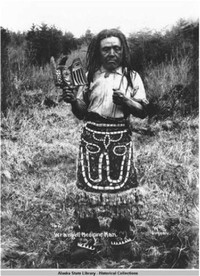

All shamans are gone from the Tlingit today and their practices will likely never be revived, although shaman spirit songs are still done in their ceremonies, and their stories re-told at those times.

Another version suggests the Tlingit people crossed into Alaska by way of the Bering land bridge.

Three attributes that Tlingits value in a person are hardness, dryness, and heat.

Today, some young Tlingits look back towards what their ancestors believed, for inspiration, security, and a sense of identity.

A number of both well-known and undistinguished European explorers investigated Lingнt Aanн and encountered the Tlingit in the earliest days of contact.

The corporation in the Tlingit region is Sealaska, Inc. which serves the Tlingit as well as the Haida in Alaska.

The Tlingit culture is multifaceted and complex, a characteristic of Northwest Pacific Coast peoples with access to easily exploited rich resources.

The Tlingit language is well known not only for its complex grammar and sound system but also for using certain phonemes which are not heard in almost any other language.

Sitka National Historical Park was established on the battle site on October 18, 1972 "to commemorate the Tlingit and Russian experiences in Alaska."

Contemporary Tlingit continue to live in areas spread across Alaska and Canada.